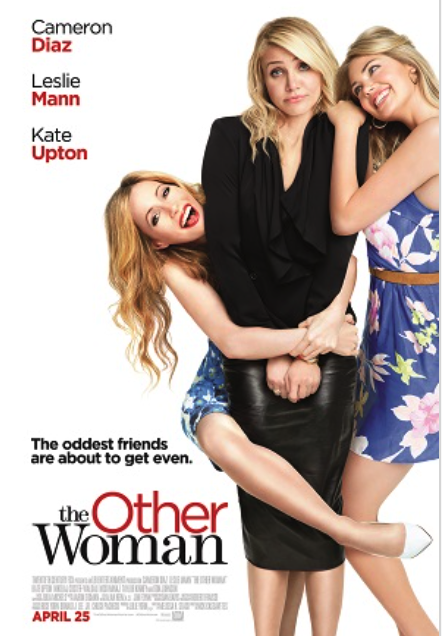

In the film The Other Woman, the character played by Kate Upton uses the potential of having chlamydia as a way to excuse herself from having sex with the villain who then promptly takes the antibiotic azithromycin (Z-Pak) and offers it to his wife because something "nasty" is going around.

With 1.4 million cases reported in 2013 (an 2-fold underestimation) it is clear that people in real life are as astute as even the villain in the movie. Chlamydia is a ubiquitous disease and is the reigning champion as the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infection in the US. It is present in about 2% of those aged 14-39 years of age. Untreated it can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility; neonates can contract chlamydial eye infections. Guidance recommends screening sexually active females under the age of 25 yearly, men who have sex men, pregnant females, and other high risk groups.

Judging by those statistics, it is clear that the transmission dynamics of this microbe seem incredibly suited to widespread dissemination through the population. The chief factor is the high rate of people without symptoms (90% of men and up to 70-95% of women) who can serve as vectors for spread of chlamydia. Also, infections of the pharynx and rectum (a Z-Pak may be less effective with rectal chlamydia) can play roles as hidden reservoirs of infection. A recent Canadian study revealed up to 13.5% of woman had rectal chlamydia, some irrespective of anal intercourse of presence of the organism at other sites.

The salient point is that infections that are asymptomatic but yet contagious will always be a challenge to control.

The movie also has another infectious disease reference--this time to pork tapeworms causing brain infections (cysticercosis), a major cause of seizures worldwide. However, the script got it wrong. Eating undercooked pork gives one an intestinal tapeworm, not the brain manifestations. If, however, one eats the tapeworm eggs found in the feces of someone with an intestinal tapeworm, they can get cysts in the brain.

Pork tapeworms and chlamydia in the same post: almost like an infectious disease version of 6 Degrees of Kevin Bacon (no pun intended).