World AIDS day is about one week away and I think it is important to thing about progress against this infectious disease. While HIV/AIDS does not grab headlines in the manner of Ebola, foodborne outbreaks, or AFM (acute flaccid myelitis) it is important to realize that it is still very impactful in the US and in the world.

In 2018, though there still remains no feasible cure or vaccine there are a few important tools that have reshaped the way it approached.

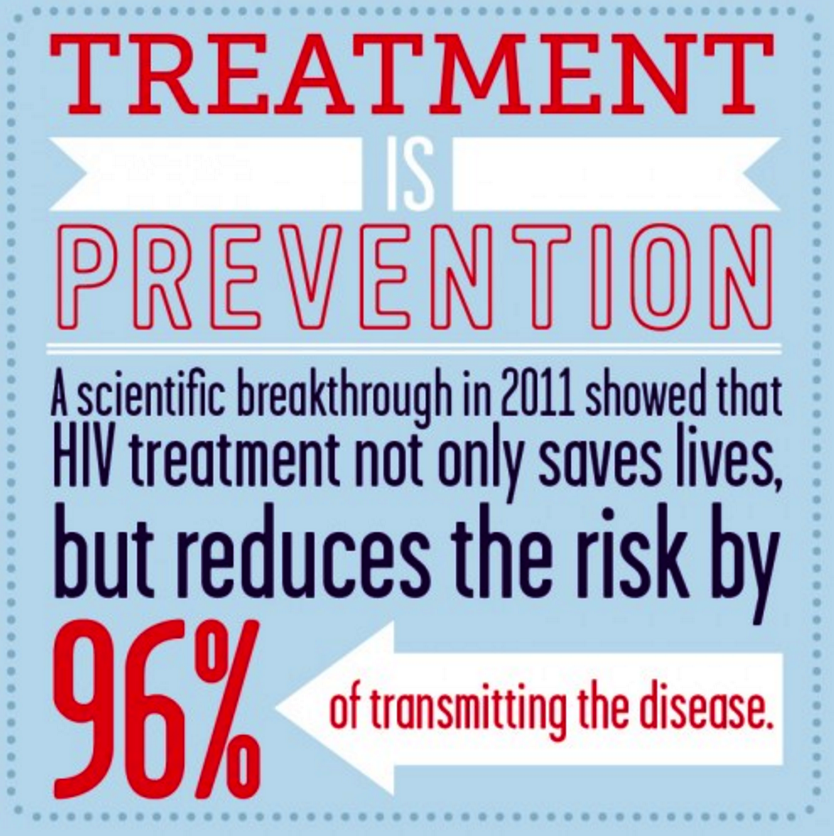

One such tool is antiretroviral therapy. Many people realize that effective treatment cocktails have transformed HIV from a death sentence to a manageable chronic illness, but they do more than that. When someone is on antiretroviral therapy and their viral load (the amount of virus detectable in their blood) is undetectable. They are no longer contagious. Undetectable = Untransmittable (U = U). This means that treatment is prevention as those on therapy are unable to infect others.

A second tool, is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PrEP is a means of protecting oneself from contracting HIV by taking two antiretroviral medications on a regular basis so if one encounters the virus during an activity such as sex, the drugs prevent infection from taking hold. While not a panacea, it is an unequivocal advance in HIV prevention and its scale up could make a significant dent in new HIV infections.

When most people think of HIV, they think of it is as the global problem that it is. However, the global pandemic is really the aggregation of local cases and outbreaks. In the Pittsburgh area, where I live and practice, there are several groups working to curtail infections locally. One such group, that I am part of, is AIDS Free Pittsburgh. This organization’s aim is to decrease new HIV diagnoses in Allegheny County, in which Pittsburgh is located, by 75% from 2015 levels (142 cases) and eliminate AIDS in the county by 2020.

Recent data shows that their concentrated approach of working with strategic partners to increase testing, increase linkage to care, and enhance PrEP prescribing has been effective. In 2017, just 100 new diagnoses of HIV were made in the county — representing a 30% decrease since the formation of the organization — with 26 new AIDS diagnoses.

Looking at the data, however, there clearly are epidemiological opportunities to further decrease the force of infection in the county. For example, 80% of new infections were in males with 61% being in men who have sex with men — a prime target for PrEP. In fact, it seems the 75% goal could almost be met with prevention activity in this subgroup. Injection drug use accounted for 8% of new infections — another transmission category easily amenable to interdiction through needle exchange.

The point I am trying to make is that the HIV crisis can be addressed in a meaningful way just by looking at one’s local epidemiology and tailoring approaches to address the nuances of the area. Other communities, would do well to learn from the example of AIDS Free Pittsburgh.