It can't be emphasized enough the dengue fever is a deadly viral infection that exacts a considerable burden on the world. Any tool to diminish this impact would be welcomed by the world. This mosquito-borne virus has a unique aspect about its pathophysiology that makes it especially intriguing and difficult to develop a vaccine against. There are 4 types or strains of dengue virus (maybe five) that circulate and it has been shown that antibody-based immunity to one strain enhances the severity of subsequent infections with the other strains. This phenomenon is known as antibody-dependent enhancement and is what accounts for severe dengue.

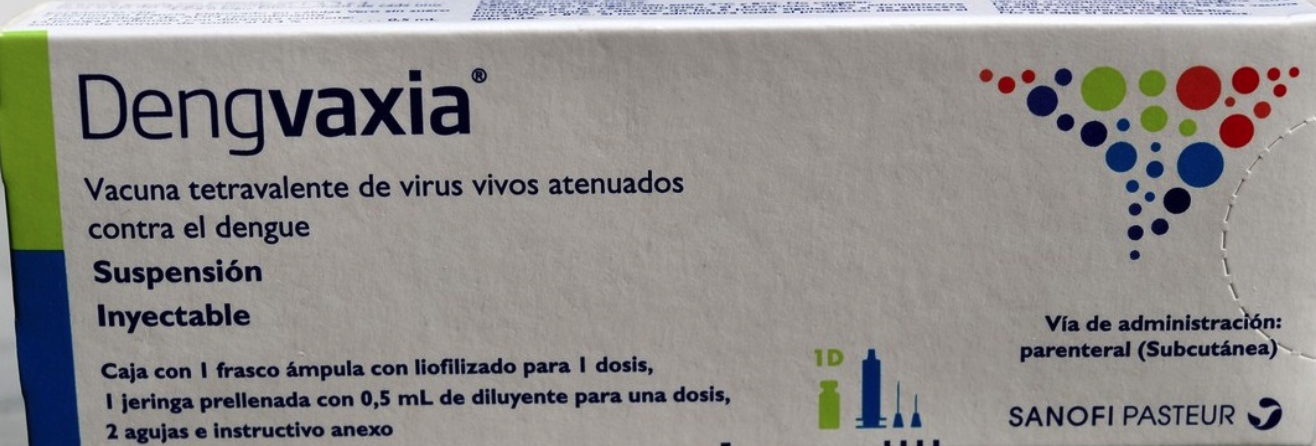

Because of this capacity of dengue, it is essential that any vaccine not induce antibodies that lead to enhancement of infection. The only dengue vaccine on the market to seemingly clear this hurdle was Sanofi Pasteur's Dengvaxia which has been licensed in several countries (but not the US). This vaccine, based on a yellow fever vaccine platform, is protective against 4 strains of dengue.

Dengvaxia has been in the news because of new longer term data showing that in those with no prior immunity to dengue, the vaccine increases the chances that infection will lead to severe disease. Perhaps vaccine induced antibodies -- in the absence of any naturally formed antibodies -- are enhancing. Interestingly, in the clinical trials of this vaccine an increased rate of hospitalization and severe dengue was noted in children less than 9 years of age which restricted its use to those above 9. I wonder if this is because those younger than 9 are more likely to have escaped natural dengue infection and be liable to develop severe dengue due to vaccine-induced antibodies. Of course, some people may reach 9 years of age and escape natural infection and have a similar risk as those below age 9.

It may be that restriction of the vaccine to those with laboratory confirmed dengue -- irrespective of age -- will be the best way to salvage this vaccine as a tool to prevent severe dengue. However, adding a lab test will considerably increase the costs and logistical difficulty of deployment. This finding also makes it very difficult to market the vaccine to travelers, most of whom will not have any natural dengue antibodies.

While this negative finding is clearly a setback for Sanofi, the dengue vaccine field, and for the countries using the vaccine it should be seen as a validation for the rigor of post-licensure vaccine safety testing in which this signal was uncovered and openly publicized. This finding should not be misinterpreted as some way to bolster the veracity of the anti-vaccine movement (which I am sure is inevitable) and be used to smear other vaccines to which this finding is wholly inapplicable.